DuckDB: The Indispensable Geospatial Tool You Didn't Know You Were Missing

Anyone who has been following me closely the last couple of months has picked up that I’m pretty excited by DuckDB. In this post, I’ll delve deep into my experience with it, exploring what makes it awesome and its transformative potential, especially for the geospatial world. Hopefully, by the end of the post, you’ll be convinced to try it out yourself.

My Path to DuckDB

So I think I first heard about DuckDB maybe six months ago, mentioned by people who are more aware of the bleeding edge than I, like Kyle Barron. My thought on hearing about it was probably similar to the majority of people reading this – why the heck would I need a new database? How could this new random thing possibly be better than the vast array of tools I already have access to? I’m not the type who’s constantly jumping to new technologies and generally didn’t think that anything about a database could really impress me. But DuckDB somehow has become one of the pieces of technology – I gush about it to anyone who could possibly benefit. Despite my attempts, I struggled to convince people to actually use it. That was until my long-time collaborator, Tim, gave it a try. His experience mirrored my sentiments:

So now I’m newly inspired to convince everyone to give it a try, including you, dear reader.

My story is that I came to DuckDB after spending a lot of time with GeoPandas and PostGIS, in my initial attempt to create this cloud-native distribution of Google’s Open Buildings dataset on the awesome Source Cooperative. The key thing I wanted to do was partition the dataset and start a discussion to learn about it. Max Gabrielsson, the author of the DuckDB spatial extension had been following GeoParquet, and suggested that a popular use case for it is partitioning of Parquet files – exactly the problem I was grappling with. It didn’t handle what I was looking to do, but it was super easy to install and start playing with. The nicest thing for me was that I could just treat my Parquet files directly as ’the database’ – I didn’t have to load them up in a big import step and then export them out. You can just do:

select * from '0c5_buildings.parquet'

Even cooler is to do a whole directory at once:

select * from 'buildings/*.parquet'

I had also been really struggling with this 100 gigabyte dataset – trying to do it all in Pandas led to lots of out of memory errors. I had loaded it up in PostGIS, which did let me work with it and ultimately accomplished my goal, but many of the steps were quite slow. Indeed a count(*) took minutes to respond, and just loading and writing out all the data also took half a day. Even ogr2ogr struggled with out of memory errors for some of my attempted operations.

When I found DuckDB I had mostly completed my project, but it immediately impressed me. I was able to do some of the same operations as other tools but instead of running out of memory, it’d just seamlessly start making use of disk instead of hogging up all the memory. The other thing that blew me away was being able to do the count of 800 million rows. I could load all the Parquet files up in a single 100 gigabyte database and get the count in near instant times, which hugely contrasted with PostGIS. I’d guess there’s a way to get an approximate count much faster with PostGIS but,

- It isn’t the default (so by default I’m waiting for minutes)

- I did need the exact count to make sure I transformed every building properly.

I could even just skip the step of loading the data into DuckDB and just get the count of all the Parquet files in my directory, also in sub-second times. The other thing that’s pretty clear with DuckDB is that it’s always firing ‘on all cylinders’ – it consistently uses all the cores of my laptop, and so just generally crunches things a lot faster. After this experience, I started to reach for DuckDB more to see how it’d do in more of my data-related tasks, and it’s continued to be awesome.

It’s the little things

In this section, I’d like to explain all the reasons I like DuckDB so much. My overall sense is that there really isn’t any single ‘killer feature’, it’s just a preponderance of small and medium-sized things, that all add to just a really great user experience. But I’ll highlight the ones that I noticed.

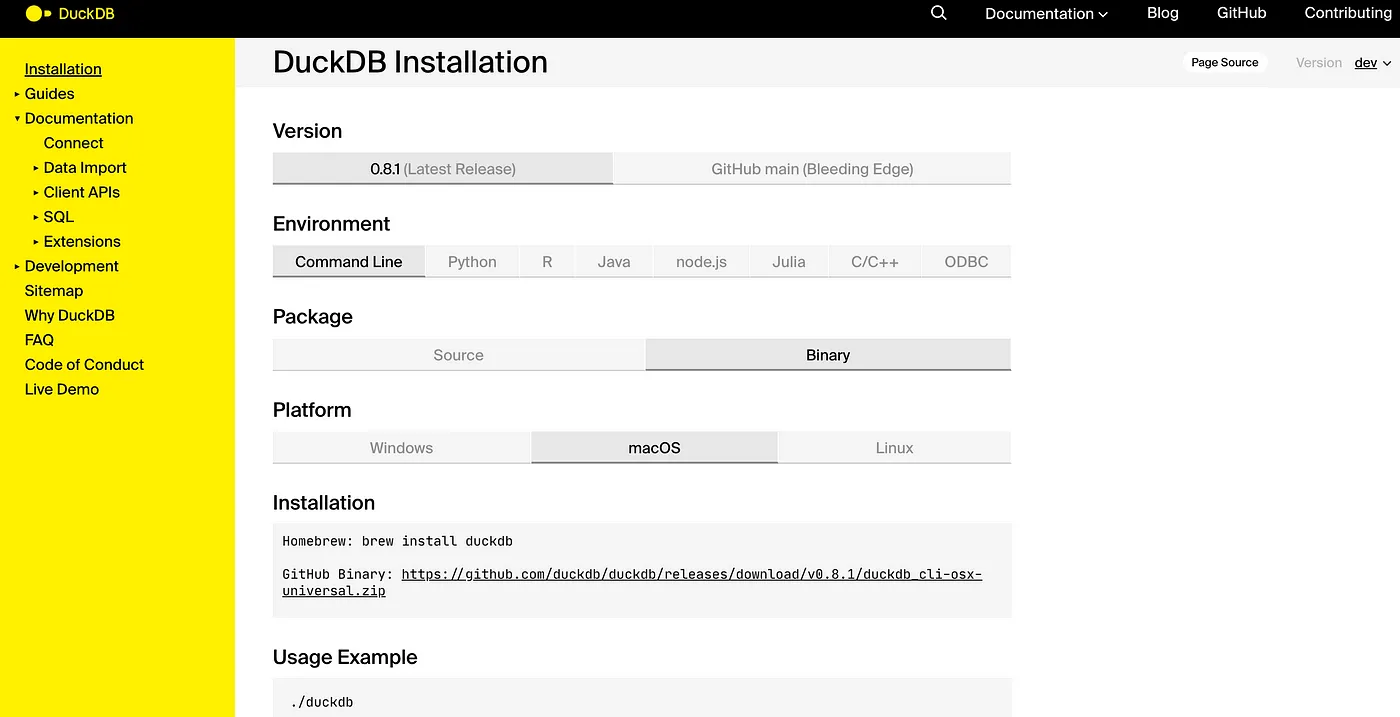

Ease of Getting Started

There was no friction for me to get going. There were lots of options to install DuckDB, and it all ‘just worked’ – I had it running on my command-line in no time.

You just type 'duckdb' and you can start writing SQL and be instantly working with Parquet. When you’re ready you can turn it into a table. If you want to save the table to disk then you just supply a filename like duckdb mydata.duckdb and it’s done. Then later when I started to use it with Python it was just a pip install duckdb to install it. In Python, I could just treat it the same as any other database, but with much easier connection parameters – I didn’t need to remember my port, database name, user name, etc. Installing the extensions was also a breeze, just:

INSTALL spatial;

LOAD spatial;

This installs all the format support of GDAL/OGR, but I suspect it is much less likely to foobar your GDAL installation by managing and using it more locally to DuckDB.

Ergonomics

There are lots of nice little touches that make it much more usable. The following highlights two of my favorites:

The first is the progress bar, showing the percentage done of the command. This is in no way essential, but it’s really nice when you’re running a longer query to get some sense of if it’ll finish in a few seconds or if it’s going to be minutes or even longer. I won’t say that it’s always perfect, indeed when you’re writing out geospatial formats it’ll get to 99% and then pause there awhile as it lets OGR do its thing. But I really appreciate that it tries.

The second is what gets returned when you do 'select * from' – it aims to nicely fill your terminal, showing as many columns as it can fit. If your terminal isn’t as wide it’ll show less columns, and always show the total number of columns, and the number shown. My experience with other databases is often more like this:

(I’m mostly hitting spacebar a bunch to try to scroll down, but never get anywhere so hit ‘q’ to quit)

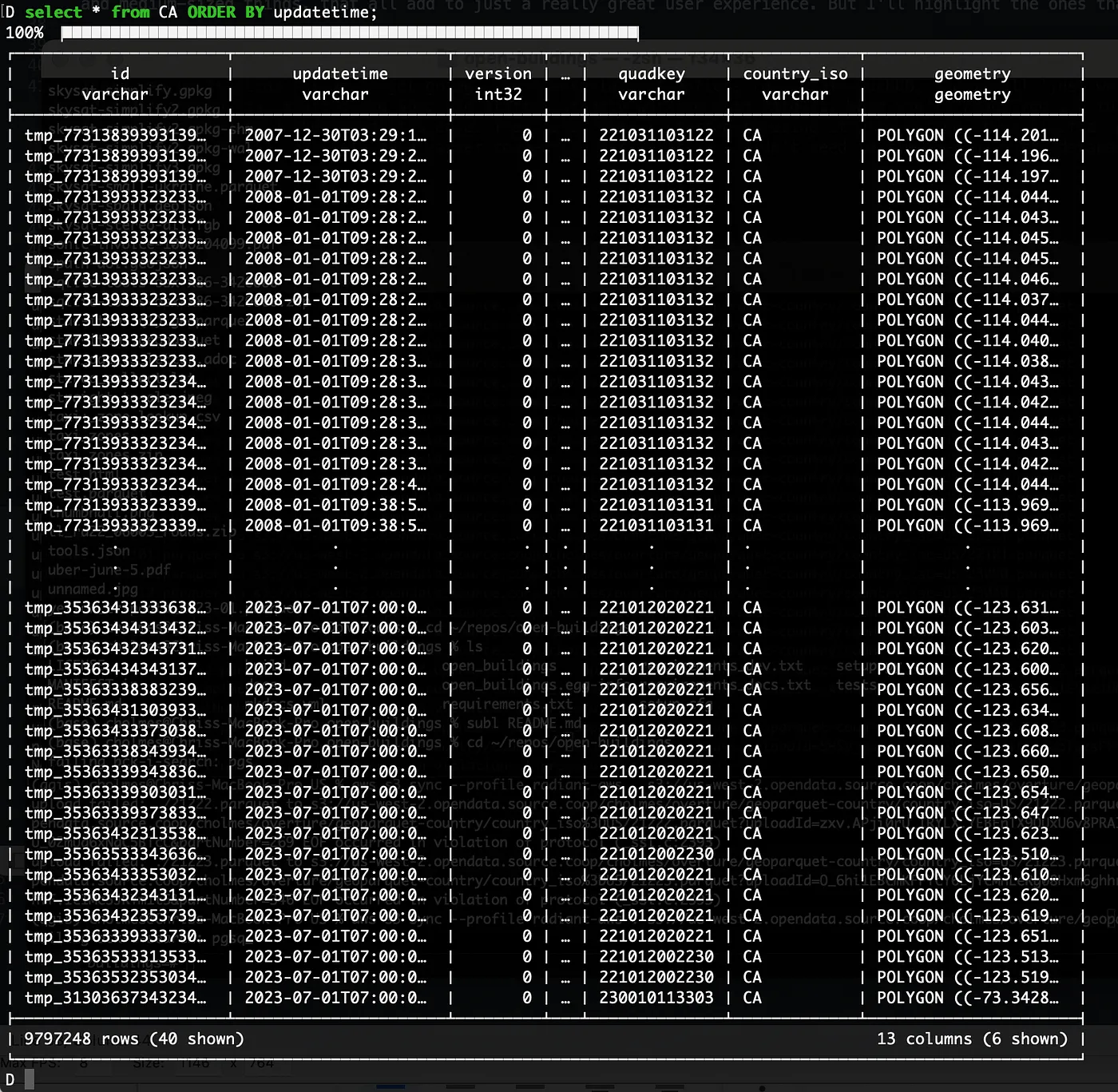

I’m not sure how DuckDB determines which to show, but they’re often the ones I want to see, and it’s easy to just make a new SQL statement to show exactly the ones you want to see. It also shows you the first 20 rows and the last 20 rows. If you do a ORDER BY then you can easily see the range:

I also snuck in a third:

CREATE TABLE CA AS (select * EXCLUDE geometry, ST_GeomFromWKB(geometry) AS geometry from 'CA.parquet');

This EXCLUDE geometry is one of those commands you’ve always wanted in SQL but never had a way to do it. In most SQL, if you want to leave off one column then you need to name all the other ones, even if it’s like 20 columns with obscure names. It’s cool to see nice innovations in core SQL. And the innovations from DuckDB are spreading, like GROUP BY ALL, which I haven’t really used yet. It was recently announced in Snowflake, but it originated in DuckDB. A recent blog post called Even Friendlier SQL has lots more tips and tricks, including one I’m starting to use: you can just say FROM my_table; instead of select * from my_table!

There are lots of other little touches that can be hard to remember but all add up to just a pleasant experience. Things like autocomplete and using ctrl-c to quit the operation, and again to quit the DuckDB command interface – the timing is just well done, where I never accidentally quit when I don’t want to. Another thing I haven’t yet explored that I’m excited about is doing unix piping in and out of DuckDB in the command-line. I’ve not yet explored this, but it seems incredibly powerful.

Just a file on disk

Another thing I really like is how easy it is to switch between interacting with the database on the command-line and in Python. Since the entire database is just a location on disk I can easily start up the database and inspect it to confirm what I did programmatically. It’s also super easy to move your database, you just move it like any other file, and connect in the new location. The other thing I really appreciate is you can easily see how much space your database is taking up – since it’s just a file you can view it and delete it just like others. It’s not buried in ‘system’ like my tables in PostGIS, and it also doesn’t need to be running as a service to connect to it. (I realize that SQLite offers up this type of flexibility, but it never got into my day to day workflows).

Remote file support

DuckDB also has the ability to work in a completely Cloud-Native Geospatial manner – you can treat remote files just like they’re on disk, and DuckDB will use range requests to optimize querying them. This is done with the awesome httpfs extension, which makes it super easy to connect to remote data. It can point to any https file. The thing I really love is how easy it is to connect to S3 (or interfaces supporting S3, and I think native Azure support is coming soon).

load httpfs; select * from 'https://data.source.coop/cholmes/overture/geoparquet-country-quad-2/BM.parquet';

I mostly work with open data, and for years it was a struggle for me to either figure out the equivalent https location for an S3 location, or to get my Amazon account all set up when I just wanted to pull down some data. With DuckDB you don’t have to configure anything, you can just point at S3 and start working (I concede that Amazon’s Open Data does now have the simple one liner for unauthenticated access, but I think that’s newer, and DuckDB still feels easier).

With S3 you can also do ‘glob’ matching, querying a whole directory or set of directories in one call to treat it as a single table call.

select count(*) from read_parquet('s3://us-west-2.opendata.source.coop/cholmes/overture/geoparquet-refined/*.parquet');

With really big datasets it can sometimes be a bit slow to do every call remotely, but it’s also super easy to just create a table from any remote query and then you have it locally where you can continue to query it.

Parquet Support

DuckDB also really shines with Parquet. The coolest thing about it is that you can just treat any Parquet file or set of Parquet files as a table, without actually ‘importing’ it into the database. If it’s under 500 megabytes / a couple million rows then any query feels fairly instant (if it’s more then it’s just a few seconds to create a table). The syntax is (as usual) just so intuitive:

select * from 'JP.parquet';

select * from '/Users/cholmes/geodata/overture/*.parquet'

If your file doesn’t end with .parquet you can use the equivalent read_parquet command: select * from read_parquet(*);

And this also works if you’re working with remote files, though performance depends more on your bandwidth. You can also easily write out new Parquet files, with lots of great options like controlling the size of row groups and doing partitioned writes. And you can do this all in one call, without ever instantiating a table.

COPY (select * from 'JP.parquet' ORDER BY quadkey) TO 'JP-sorted.parquet' (FORMAT PARQUET, ROW_GROUP_SIZE 10000)

Performance

The one thing that I think can be considered more than a ’little thing’ is simply the overall performance of DuckDB. I wrote a post on how it performed versus Pandas and GDAL/OGR for writing out data. There are lots of other aspects of performance to explore, but in my anecdotal experience, it’s faster than just about any other tool I try. I believe the main thing behind this is that it’s built for the ground-up for multi-core systems, and I’m on an M2 mac that I believe usually has a lot of idle CPU power.

The other thing behind it is just the inherent advantages of a columnar data store for data analysis – which is most of what I’m doing. DuckDB wouldn’t be what you’d use on a scale-out production system that’s write heavy, but that’s not what I’m doing. For just processing data on my laptop it feels like an ideal tool. The columnar nature of it enables things like the ‘count’ to always be sub-second responses, even with hundreds of millions of records. It’s just nice to not have to wait.

The other bit that’s really nice is how it’s rarely memory constrained. Even when you’re using it in ‘in-memory’ mode (i.e. not saving a specific database file), it’ll start writing out temp files to disk when it hits memory limits. I have hit some cases where I do get out of memory errors – I think it’s mostly when I’m trying to process big (8 gigabyte+) files directly to and from Parquet. But doing similar operations by creating huge databases on disk (like 150 gig+) and then writing out seems to go fine. The core team seems to be continually pushing on this, so I think 0.9 may have improvements that make it even better for huge datasets.

Spatial support

DuckDB’s spatial support is quite new, and not yet super mature. But it’s made one of the best initial releases of spatial support, by leveraging a lot of great open source software. The center of that is GEOS, which is the same spatial engine that PostGIS uses. This has enabled DuckDB to implement all the core spatial operations, so you can do any spatial comparison, and use those for spatial joins. You can convert Well Known Text and Well Known Binary with ease, or even X and Y columns – the conversion functions make it quite easy to ‘spatialize’ any existing Parquet data and do geospatial processing with it.

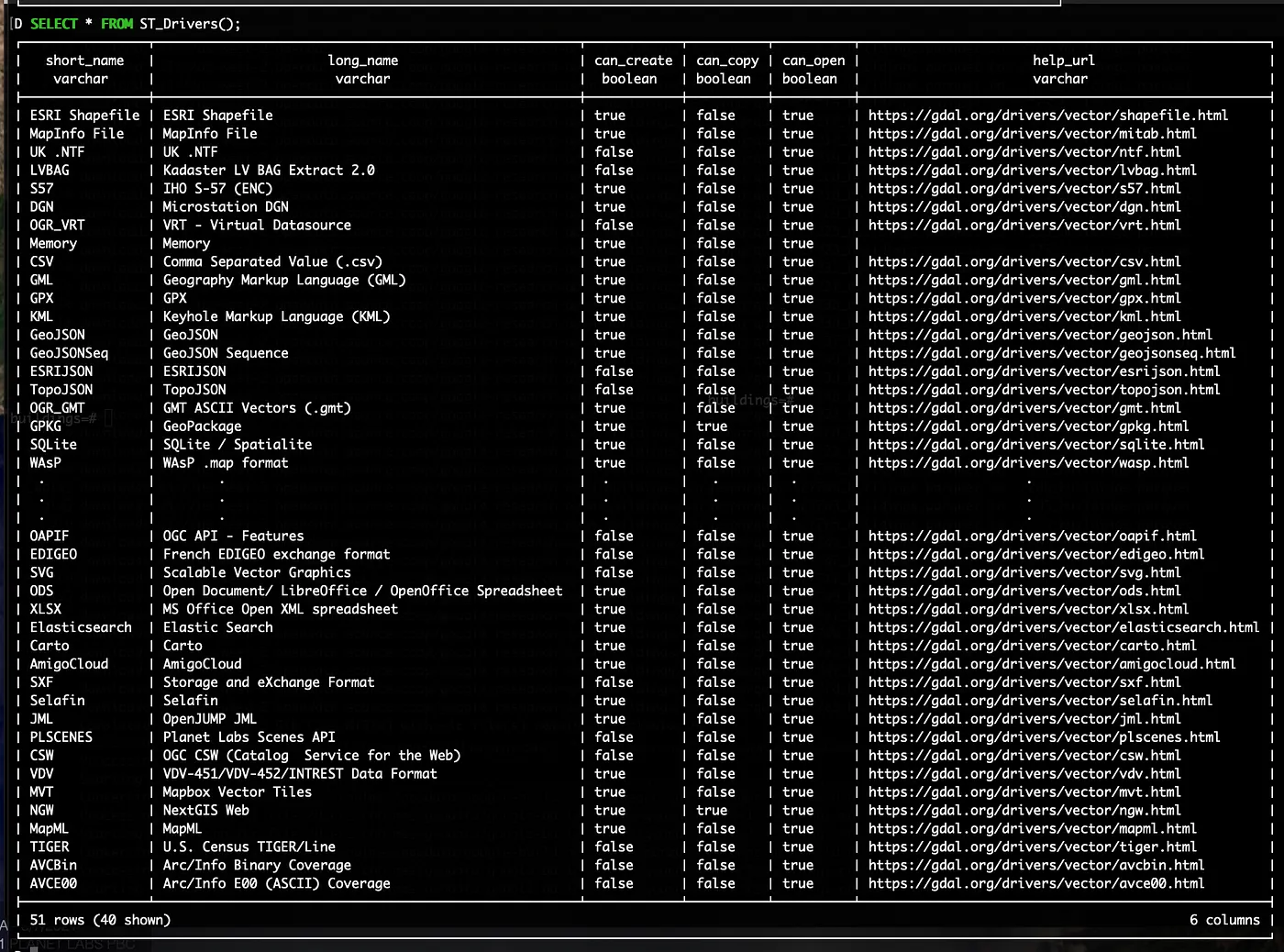

The other open source library they leveraged to great effect was OGR/GDAL. You can easily import or export any format that OGR supports, completely within DuckDB SQL commands.

Drivers supported in a typical DuckDB spatial instance

Drivers supported in a typical DuckDB spatial instanceThis makes it super easy to get data into and out of DuckDB, and to also just use it as a processing engine instead of a full blown database where you need to store the data. Those deep in the spatial world will likely question why this is even necessary – why wouldn’t you just use GDAL itself to load and export data?

My opinion is that we in the geospatial world need to meet people more than halfway, enabling them to stay in their existing workflows and toolsets. Including GDAL/OGR makes it far easier for people who just dabble in geospatial data to easily export their data into any format a geo person might want, and also really easy to import any format of data that might be useful to them. It’s just:

load spatial;

CREATE TABLE my_table AS SELECT * FROM ST_Read('filename.geojson');

It’s also nice that it’s embedded and more limited than a full GDAL/OGR install, as I suspect it’ll make it less likely to get GDAL in a messed up state, which I’ve had happen a number of times.

Spatial ‘opportunities’

There are definitely some areas where its immature status shows. The geometry columns don’t have any persistent projection information, though you can perform reprojection if you do know what projection your data is in. The big thing that is missing though is the ability to write out the projection information in the output format you’re writing to. This could likely be done with just an argument to the GDAL writer, so hopefully will come soon. GeoParquet is not yet supported as an output, but it is trivial to read, and quite easy to write a ‘compatible’ parquet, and then fix it with GPQ (or any other good GeoParquet tool). My hope is that the native Parquet writer will seamlessly implement GeoParquet, so that if you have a spatial column it will just write out the proper GeoParquet metadata in the standard Parquet output (which should then be the fastest geospatial output format).

The biggest thing missing compared to more mature spatial databases is spatial indexing. I’ve actually been surprised by how effectively it’s performed in my work without this. I think I don’t actually do a ton of spatial joins. And DuckDB’s overall speed and performance allow it to just use brute force to chunk through beefy spatial calculations pretty quickly even without the spatial index. I’ve also been just adding a quadkey and then doing ORDER BY quadkey which has worked pretty well.

More mature spatial databases do have a larger array of useful spatial operations, and they continue to add more great features, so it will take DuckDB quite a long time to fully catch up. But the beauty of open source is that many of the core libraries are shared, so innovations in one can easily show up in another. And the DuckDB team has been quite innovative, so I suspect we may well see some cool ideas flowing from them to other spatial databases.

If you want to get started with DuckDB for geospatial there’s a growing number of resources. The post that got me started was this post from Mark Litwintschik. I also put together a tutorial for using DuckDB to access my cloud-native geo distribution of Google Open Buildings on Source Cooperative. And I’ve not yet turned it into a proper tutorial yet, but as I processed the Overture data I started recording the queries I built so that I could easily revisit them, so feel free to peruse those for ideas as well.

Potential for geospatial

There are a lot of potential ways I think DuckDB could have an impact in our spatial world, and indeed has the potential to help the spatial world have a bigger impact in the broader data science, business intelligence, and data engineering worlds.

The core thing that got me interested in it is the potential for enabling Cloud-Native Geospatial workflows. The traditional geospatial architecture is to have a big database on a server with an API on top of it. It is dependent on an organization having the resources and skills to keep this server running 24/7, and to scale it so it doesn’t go down if it’s popular. The ’even more traditional’ architecture is to have a bunch of GIS files on an FTP or HTTP server that people download and load up in their desktop GIS. DuckDB with well partitioned GeoParquet opens up a third way, in the same way that Cloud-Optimized GeoTIFF’s (COG’s) allowed you to make active use of huge sets of raster data sitting on object stores. You can easily select the subset of data that you want directly through DuckDB:

select * from read_parquet('s3://us-west-2.opendata.source.coop/cholmes/overture/geoparquet-country-quad/*/*.parquet') WHERE quadkey LIKE '02331313%' AND ST_Within(ST_GeomFromWKB(geometry), ST_GeomFromText('POLYGON ((-90.791811 14.756807, -90.296839 14.756807, -90.296839 14.394004, -90.791811 14.394004, -90.791811 14.756807))')))

I’ll explore this whole thread in another post, but I think there’s the potential for a new mode of distributing global-scale geospatial data. And DuckDB will be one of the more compelling tools to access it. It’s not just that DuckDB is a great command-line and Python tool, but there’s also a brewing revolution with WASM, to run more and more powerful applications in the browser. DuckDB is easily run as WASM, so you can imagine a new class of analytic geospatial applications that are entirely in the browser.

There’s also a good chance it could be an upgraded successor to SQLite / Spatialite / GeoPackage. There’s a lot of geospatial tools that embed sqlite and use it for spatial processing. DuckDB can be used in a similar, but in most analytic use cases it will be much faster since it’s a columnar database instead of a row-oriented one. And in general, it incorporates a bevy of cutting edge database ideas, so performs substantially faster. Indeed you could even see a ‘GeoPackage 2.0’ that just swaps in DuckDB for SQLite.

It could also serve as a powerful engine embedded in tools like QGIS. You could see a nice set of spatial operations enabled by DuckDB inside of QGIS, using it as an engine to better take advantage of all of a computer’s cores. I could also see QGIS evolve to be the ideal front-end for Cloud Native Geospatial datasets, letting users instantly start the browser and analyze cloud data, seamlessly downloading it and caching it when necessary, with DuckDB as the engine to enable it.

Expanding Geospatial Impact

While I think DuckDB can be a great tool in our spatial world, I think it has even more potential to help bring spatial into other worlds. The next generation of business intelligence tools (like Rill and Omni) is built on DuckDB, and it’s becoming the favorite tool of general data scientists. Having great spatial support in DuckDB and in Parquet with GeoParquet enables a really easy path for a data scientist to start working with spatial data. So we in the spatial world can ride DuckDB’s momentum and the next generation of data tools will naturally have great geospatial support. This trend has started with Snowflake and BigQuery, but it’s even better to have an awesome open source data tool like DuckDB.

I believe that the spatial world is still a niche – the vast majority of data analysis done by organizations does not include geospatial analysis, though in many cases it could bring some additional insight. I think it’s because of the long standing belief that ‘spatial is special’, that you need a set of special tools, and the data must be managed in its own way. If we can make spatial a simple ‘join’ that any data science can tap into, with a nice, incremental learning curve where we show value each step of the way, then I believe spatial can have a much bigger impact than it does today. I think it’s great that DuckDB uses GDAL/OGR to be compatible with the spatial world, but I really love the fact that it doesn’t make people ’learn GDAL’ – they can continue using SQL, which they’ve invested years in. We need to meet people more than halfway, and I think GDAL/OGR and GEOS within DuckDB do that really well.

What’s next for DuckDB and Spatial?

There are a ton of exciting things coming in DuckDB, and lots of work to make the spatial extension totally awesome. I’m really excited about DuckDB supporting Iceberg in 0.9, and I’m sure there will be even more performance improvements in that release. Top of the list for spatial advances is native GeoParquet support, and better handling of coordinate references and spatial indices, and I know the spatial extension author has a lot of ideas for even more. Unfortunately, much of the work is paused, in favor of funded contracts. I’m hoping to try to do some fundraising to help push DuckDB’s spatial support forward – if you or your organization is potentially interested then please get in touch.

Closing Thoughts

One thing I do want to make clear is that I still absolutely love PostGIS, and am not trying to convince anyone to just drop it in favor of DuckDB. When you need a transaction-oriented OLTP database nothing will come close to PostgreSQL, and PostGIS’s 20 year head start on spatial support means its depth of functionality will be incredibly hard to match (for more on the history of PostGIS check out this recent podcast on Why People Care About Postgis And Postgres). PostGIS introduced the power of using SQL for spatial analysis, showing that you could do in seconds or minutes what expensive desktop GIS software would take hours or days to do. I think DuckDB will help accelerate that trend, by making it even faster and easier when you’re working locally. I’m also excited by DuckDB and PostGIS potentially spurring one another to be better. I worked on GeoServer when MapServer was clearly the dominant geospatial web server, and I’m quite certain that the two projects pushed one another to be better.

And finally – call to action. Give DuckDB a try! If you’ve made it all the way to the end of this post then it’s definitely worth just downloading it and playing with it. It can be hard to find that first project where you think it’ll make sense, but trust me – after you get over the hump you’ll start seeing more places. It really shines when you want to read in remote data on S3, like the data I’ve been putting up on Source Cooperative, and is great for lots of data transformation tasks. And any task that you’re using Pandas for today will likely perform better with DuckDB.